Gambling Across Cultures: Mapping Worldwide Occurrence and Learning from Ethnographic Comparison

Gambling Across Cultures: Mapping Worldwide Occurrence and Learning from Ethnographic Comparison. PER BINDE. CEFOS, University of Gothenburg. P.O. Box 720. SE-40530 Göteborg. Sweden.

ABSTRACT : Gambling Across Cultures: Mapping Worldwide Occurrence and Learning from Ethnographic Comparison

This paper first maps the distribution of indigenous gambling in cultures around the world. On the basis of extensive ethnographic and historical evidence, it is concluded that gambling is not a universal phenomenon; prior to the era of European colonisation, non-gambling societies appear to have covered large areas of the globe. The pattern of gambling and non-gambling peoples and nations invites speculation and investigation. The second part of the paper reviews and critically discusses statistical cross-cultural studies that have aimed to uncover factors that promote or restrain the playing of games of chance and the practice of gambling. Some of these factors, which allow us to predict to a certain extent the presence and intensity of gambling in societies, are: the presence of commercially used money, social inequality, societal complexity, and the presence of certain kinds of competitive inter-tribal relations.

Introduction

Sweeping statements on the universality of gambling are common in century-old literature, statements such as: ‘Gaming is a universal thing—the characteristic of the human biped all the world over’ (Steinmetz, 1870, Vol. 1, p. 4); ‘Gambling seems to be indigenous among all races’ (France, 1902, p. 364); and ‘Games of chance are as old and as wide-spread as humanity’ (Paton, 1913, p. 163). In modern scientific literature one quite often encounters the understanding that gambling is a ‘universal phenomenon’ (Kassinove, 1999), occurring in ‘. . . nearly all societies and every period’ (Abt et al., 1985, p. 1), and that there is a ‘... universal desire to gamble’ (Ignatin and Smith, 1976, p. 74). This opinion is also propagated by the gambling industry as it presents gambling as something inherent in human nature and, therefore, unavoidable or even necessary for our well-being.

We need look no further back in time than a century or two, however, to find that there were many peoples of the world who did not practice gambling and who probably never had. Assuming that the distribution of gambling and non-gambling peoples at various points in history has not been random, the distribution can be scrutinised for regularities. Such regularities would say something about the nature of gambling, explaining (or at least illuminating) why some peoples have gambled and others not, and why some peoples, who earlier had not gambled at a certain time in history, began to gamble.

This article will begin by mapping the occurrence of indigenous gambling in the precolonial world. Then it will review cross-cultural statistical studies of gaming and gambling, discussing the main findings of these studies with regard to factors that promote or restrain the occurrence of games of chance and gambling. After summarising the results of these cross-cultural studies, the conclusion is offered that while gambling is a remarkably flexible way of redistributing wealth, there are several general factors that influence the likelihood of gambling being practiced in a certain society.

Mapping Gambling Worldwide

The following outline of indigenous gambling is based on information extracted from a number of anthropological publications that discuss the prevalence of gambling worldwide or on a specific continent (Cooper, 1941, 1949; Culin, 1907; Kroeber, 1948; Price, 1972; Reefe, 1987), as well as from ethnographic and historical texts relating to particular peoples.

‘Gambling’ is understood as the established practice of staking money or other valuables on games or events of an uncertain outcome. The term ‘indigenous’ refers to gambling that, among non-Western peoples, was practiced prior to extensive contact with the West. It does not necessarily mean that gambling or specific gambling games were invented locally; these may well have originated in other peoples in the region and been adapted to local culture. Cultural elements have spread from society to society since the dawn of history; it is, therefore in many cases, impossible to speak of ‘purely indigenous’ gambling. For numerous peoples, however, extensive contact with the West implied a marked discontinuity with their former ways of life and the beginning of a process that has lead to their integration in the present global system of trade and communication. It is a shift typically associated with a decisive step in societal development from pre-capitalist to capitalist, from traditional to modern, and from local to national and then to global. ‘Indigenous gambling’ is, thus, gambling as it appeared in various cultures of the world before the radical shifts that Western colonisation and capitalist expansion brought about. The term is used much in the same sense as the concept ‘indigenous religion’.

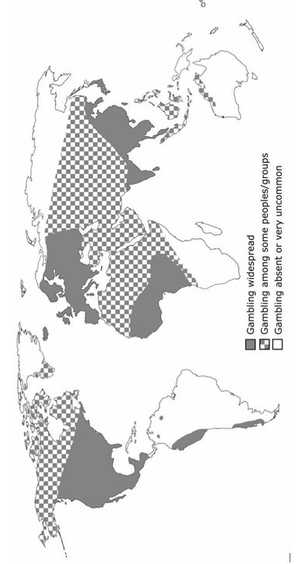

Often contact with the West implied that colonialists, explorers or ethnographers wrote records of traditional culture. Regarding some parts of the world, such as the Americas, there is relatively good ethnographic documentation of gambling. However, information on other parts of the world, such as Africa, the Muslim countries, and Central Asia, is fragmentary and also difficult to locate since it typically is scattered among various historical and ethnographic texts and often published in languages other than English. It is nevertheless possible to obtain an approximate picture of the main gambling and non-gambling regions of the pre-colonial world. This picture is presented in Figure 1, which appears to be the first of its kind to be published.

The presence of gambling in Europe and regions that had long had contact with European cultures (such as North Africa and the Middle East) is shown in approximately 1500 AD, immediately before the colonial era. Areas where gambling was widespread are indicated by solid black; areas where only some peoples, tribes or groups gambled are represented by a chequered pattern; and areas with no gambling are left blank. Let us now read the map from west to east, starting in South America.

Figure 1. Approximate prevalence of indigenous gambling

South America

The anthropologist John Cooper (1949) provides an excellent overview of the prevalence of games and gambling among indigenous South American peoples. It appears that in precolonial times, gambling was primarily limited to two areas in the west: one in present-day Peru and Ecuador, and the other farther south in the Araucanian region (in present-day central Chile), among the Picunche, Mapuche, and Huilliche peoples. In addition, gambling is documented only among a few scattered peoples in the north; Cooper mentions the Otomac (in Venezuela) and the Chibcha (in Colombia), but there might have been a few other peoples in this area who bet on rubber ball games (Stern, 1950). On the Caribbean islands, gambling, in the form of betting on ball games, was present among the Taino of Hispaniola (Alegria, 1951). Cooper (1949, p. 522) concludes, concerning the relatively few South American peoples who gambled, that: ‘all these peoples, except perhaps the Mapuche-Huilliche and Otomac, took their gambling gains very lightly’.

Central America

In Central America there was probably no or little gambling south of present-day Honduras. In the rest of Central America, betting on rubber ball games was common, as witnessed by European explorers in the sixteenth century, though it probably dates back to the Mesoamerican Classic Period (200–1000 AD) and possibly earlier. In the Post-Classic Period (1000–1530 AD), betting on these games was heavy, involving both the nobility and the common people (Stevenson Day, 2001). In the early sixteenth century, the Spanish chronicler Fray Diego Durán reported on Aztec ballgames: ‘They. . . gambled their homes, their corn granaries, their maguey plants. They sold their children in order to bet and even staked themselves and became slaves to be sacrificed later if they were not ransomed’ (cited in Stevenson Day, 2001, p. 76). These pre-Columbian ball games were part of religion and dense with cosmological symbolism (de Borhegyi, 1980; Krickeberg, 1948; Stern, 1950; Whittington, 2001).

North America

Further to the north, there was a continent of gamblers. The extensive compilation of ethnographic information presented by Steward Culin in his monumental work Games of the North American Indians (1907) shows that almost all North American tribes south of the sub-arctic area practiced some form of gambling, often with high stakes. In the sub-arctic area, non-gambling tribes appear to have been more common, as can be inferred from early ethnographic reports. For instance, the northeastern Cree, the Montagnais, and some Alaskan Athapaskans did not gamble (Cooper, 1941). As for the Inuit in the Arctic area, some groups gambled on indigenous games in the nineteenth century, and there is little that would make us believe that this was a recently acquired practice (Culin, 1907; Glassford, 1970); there are ethnographic reports however that state that other Inuit groups did not gamble (e.g. Moore, 1923).

Africa

Despite Muslim influence, in West Africa gambling was extensive and also prevalent in the area of the Congo (Zaire) River (Kroeber, 1948, p. 552; Reefe, 1987, p. 47). Gambling prevailed to a vast extent in tribal societies of the rainforest in the area ‘from southern Nigeria to the East African Lakes’ (Reefe, 1987, p. 48). For the rest of Africa south of the Sahara, reports on indigenous gambling are scant; the game mancala (or warior solo) was indeed widespread on the continent, but this strategy game was far from always accompanied by betting and gambling (e.g. Culin, 1894; Driberg, 1927). There was probably little or no gambling in the south and southeast of Africa (Cooper, 1941; Kroeber, 1948, p. 552).

The Muslim World

In mapping the prevalence of gambling, a particularly difficult problem arises concerning the Muslim world. At the end of the fifteenth century, Islam was practiced, in some form and to some extent, in the following areas: in North Africa down to a line approximately from Sierra Leone in the west to the Horn of Africa in the east, as well as along the east coast as far south as Zimbabwe; in Turkey, the Balkans, in the Middle East, and in a belt further southeast to the Bengal with the exception of southern India; in Malacca, Sumatra, Java, Lombok, Celebes and some other islands in this region.

Since gambling is explicitly forbidden in the Koran, it should not in principle be practiced by any Muslim. However, it is evident that at this time, Islam had a rather limited influence on culture and society in some parts of the vast area mentioned and, consequently, had little influence on the actual practice of gambling. Even where Islam was a religion of importance, its stand on gambling could be adapted to local traditions; indigenous versions of Islam were no doubt very different from ‘universal’ Islam. West Africa has already been mentioned as an example of an Islamic area where gambling nevertheless flourished; other areas where this was the case include the eastern parts of the Muslim world. Islam spread to Malacca, Sumatra, Java, and Celebes only after the twelfth century, and gambling, which was practiced in many areas which had contacts with India and China, was probably little affected.

In the region where Islam had been established for centuries and had the status of the tribal or state religion—i.e. in North Africa, the Middle East, Persia, and beyond to western India—the Muslim ban on gambling was of greater importance. In some areas, it was without doubt strictly observed and gambling was likely minimal. There is also the old notion in North African and Arabic cultures that games (including gambling games) are a childish activity in which adult and serious men should not engage (Rosenthal, 1975, p. 5). In other areas, however, gambling as part of local tradition was practiced despite being condemned by religion. Gambling at a low or moderate level seems to have been practiced in what is present-day Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan (Price, 1972); apparently gambling was more common in urban settings and among the more well-to-do. Therefore, the core region of the Muslim world as of the early fourteenth century as represented on the map in Figure 1 is one where gambling was practiced in some areas and not in others, or only by some groups of people.

Europe and Asia

In Europe the extent of gambling is much easier to assess. Gambling was practiced among virtually all peoples, except the Sa´mi in the north and perhaps in some minor areas of the Balkans. East of the Ural, gambling was less frequent and was probably uncommon in central and eastern Siberia (Kroeber, 1948; Price, 1972). Farther south, some peoples seem to have been gambling while others were not (Price, 1972). The Ainu of northern Japan were non-gamblers but the Tibetans, influenced by the Chinese, were a gambling people. Some sources indicate gambling among Mongolian peoples, while other sources state that there were no games for money, except by Russians and Chinese in Mongolia who are said (in the early twentieth century) to have been heavy gamblers (Price, 1972)

Continuing south, we come to China, where gambling undoubtedly is of ancient provenance. It seems to have been particularly intense in southern China, in Burma and Thailand, and prevalent among many other peoples of East and South Asia, especially those influenced by Hindu, Malay, and Chinese culture (Bankoff, 1991; Price, 1972). Other Asian peoples, such as the hunter–gatherers and small-scale tribal societies of the interior of Sumatra and Borneo, were nongamblers (Cooper, 1941; Kroeber, 1948). In India, gambling is mentioned already in the Mahabharata epos and widely practiced through the centuries despite reprobation from dogmatic Hinduism.

Oceania

In Melanesia, Australia and New Zealand there was virtually no gambling (Cooper, 1941; Kroeber, 1948). Some aboriginal groups of northern Australia gambled at cards at the time of first contact with Europeans, a practice introduced by Asian traders (Berndt and Berndt, 1947; Robinson, 1978). In Micronesia and Polynesia, only a few peoples can be assumed to have gambled (Cooper, 1941). The ancient Hawaiians, however, were certainly heavy gamblers (Culin, 1899).

Further Evidence: Frederic Pryor’s Crosscultural Study

This overview of indigenous gambling worldwide and accompanying Figure 1 is based on scattered ethnographic reports and a few summaries, some of which are based on extensive ethnographic data while others rely on more limited sets of information. An indication of the overview’s reliability is obtainable by comparing it with the actual occurrence of gambling in a set of systematically selected cultures of the world. In the 1970s, the economist Frederic Pryor conducted a number of cross-cultural statistical studies (Pryor, 1977), one subject of interest being gambling. The results of this study (Pryor, 1976) will be discussed below. A custom sample of 60 societies was used, covering 58 of the 60 distinct cultural areas of the world that were defined by the anthropologist Peter Murdock in the World Ethnographic Sample (1957). The societies sampled are mainly non- Western, most of the ethnographic source texts referring to times before extensive contact with the West, which generally means in the second half of the nineteenth century. The codingsforthe presence of gambling (‘gambling not reported’, ‘gambling reported but not an important economic activity’, and ‘gambling reported as important economic activity’) were made by Pryor himself. In Figure 2, Pryor’s data are displayed geographically so as to facilitate comparison with.

Figure 1. A list of the 60 societies and a map showing their locations is found on the inside front cover of Pryor’s book The Origin of the Economy (1977).

Compared with Figure 1, there are only a few discrepancies. In South America, the Toba of Argentina are shown as practicing some gambling; the ethnographic source for this information is from 1860 (Pryor, 1976, p. 831). However, Cooper (1949, p. 522) concludes that: ‘in the main, passionate addiction to gambling, such as is later recorded in the Araucanian, Chacoan, Pampean, and Patagonian areas, appears to be, in large part at least, a reflection of the gambling frenzy that pervaded Old World Spanish society in the 16th and l7th centuries. . .’ Toba gambling is thus unlikely to have been indigenous.

In Africa, the Tanala of Madagascar are shown as having been gambling, and gambling might well have been practiced for centuries on this island, which was a crossroad of African, Islamic, and Asian cultures.

In India, the Todas (in the northwest), the Bhil (in the south), and the Lepcha (in the northeast, partly in Bhutan) are reported to have no gambling. The Indian sub-continent is inhabited by a large number of ethnic groups with distinct cultural traditions. Although gambling has long been spread over much of this region, it was certainly not part of all local traditions. In a more detailed version of Figure 1, not only northern India but also some other parts of India would probably be marked with a chequered pattern indicating gambling among some groups, but not among others.

The non-gambling symbol on the Malay Peninsula does not refer to any larger polity of this area, but to the Semang, a Negrito people who are hunters and gatherers and probably descendants of the aboriginal population of the Malacca. On the other side of the Malacca Strait, on Sumatra, we see that gambling was important to the Batak, a people subsisting on rice cultivation. These two cases are in accord with the suggestion that the major peoples in South Asia, directly or indirectly influenced by Hindu and Chinese culture, were gamblers, but that hunter–gatherers and other small-scale societies were mainly non-gamblers.

Finally, it might be noted that in Micronesia and Polynesia, gambling is indicated on one island, Truk, and as absent on three others: Tikopia, Vanua Levu (Fiji), and New Zealand’s North Island. This is consistent with the conclusion that most peoples in the Pacific were non-gamblers, but that there were some exceptions. In another cross-cultural sample (Textor, 1967, FC 459), ‘games of chance’ were coded as present in five societies of the Insular Pacific and absent from 27 others.

The Evidence of the Two Maps

Figure 2 largely confirms the picture of the extent of indigenous gambling shown in Figure 1, since there is a possible discrepancy in only two of the 60 cases (Madagascar and Bhil in Southern India).

There might be objections that the source material of the two maps is unreliable. Much of it consists of reports from ethnographers of the past and also from early explorers and chroniclers. The texts written by these observers are products of a specific time and a certain social environment and must, therefore, be viewed in a critical and reflexive way. In modern anthropology, it has been noted that there is often, in the old ethnographical and anthropological accounts, a ‘cultural silence’ concerning certain aspects of social life. Perhaps such circumstances have resulted in gambling not being reported among a large number of peoples. There is, however, little that would lead us to assume this.

We are concerned with the quite simple question whether or not a certain people practiced gambling. The ethnographer does not ‘interpret’ the existence of gambling; he or she observes it. Having observed gambling, the ethnographer may venture into discussions of its meaning and social function, and such discussions would certainly require a reflexive consideration. As to the possible cultural ‘silence’ about gambling in older ethnographic reports, let us for instance consider North and South America. In the North American ethnographies, there is definitely no ‘silence’ about gambling; there are many detailed descriptions of gambling practices, implements, songs, and beliefs. Culin’s (1907) book Games of the North American Indians has hundreds of citations of such works. In South America, however, ethnographic reports of indigenous gambling are sparse, but this can hardly be attributed to a ‘silence’ surrounding this practice. Why should ethnographers in South America have been ‘silent’ about gambling when their colleagues in North America were not? It is much more plausible that the absence of reports of gambling in otherwise detailed ethnographies from much of South America and elsewhere indicates that there was indeed no gambling in these areas.

On the basis of substantial ethnographic and other evidence, it can be concluded that before extensive contact with the West, a large number of peoples of the world did not gamble. Figure 1 provides a general picture of the distribution of gambling and non-gambling societies. Some peoples were moderate gamblers, while others practiced gambling extensively and intensely. Some of this variation is indicated in Figure 2, presenting data from Pryor’s (1976) study.

Explaining the Geographical Distribution of Indigenous Gambling

The distribution of gambling around the world and throughout history invites speculation and investigation. Why do some peoples gamble while others do not? Are there any general factors that promote or restrain the occurrence of gambling? Why might a non-gambling people become gamblers at a certain time in history? Such questions are potentially of interest for gambling studies more generally, since their eventual answers might shed light on the nature of gambling and the motivations people have for gambling. Unfortunately, no comprehensive study has yet been undertaken to answer these questions. There are, however, a number of cross-cultural statistical studies that to varying extents are relevant and these will now be discussed.

Although the first statistical cross-cultural anthropological studies had already been conducted in the late nineteenth century, the approach began to be more widely used in the 1930s and 1940s (for overviews, see Burton and White, 1987; Ember and Ember, 1998; Naroll, 1970). The principal aim of cross-cultural comparison is to discover, explore, and confirm systemic relationships in social and cultural life. Most of the cross-cultural surveys that have been conducted (in 2001 about 1,000, according to Ember and Ember, 2001, p. 12) build on the structural-functionalistic paradigm, thus: ‘The basic assumption underlying cross-cultural research is that the elements of any culture tend over time to become functionally integrated or reciprocally adjusted to one another’ (Murdock and White, 1969, p. 329). Some of the main fields of investigation have been social organisation and kinship, cultural evolution, warfare and conflict, as well as psychological perspectives on child rearing practices, adult behaviour, and belief.

The statistical cross-cultural approach is contested. Many anthropologists hold that culture is a phenomenon that cannot fruitfully be explored by statistical methods. There has been concern over a number of methodological and theoretical problems (Burton and White, 1987; Ember and Ember, 1998), such as: what should constitute a ‘case’—a single community, a tribe, or a society; how should a representative world sample of cultures be composed; and is it at all possible to dissect a culture, identifying specific quantifiable variables that are assumed to be the ‘same’ as in other cultures? There is also the problem of coding the worldwide variety of cultural phenomena in discrete variables, a problem which is especially pertinent with respect to ‘high-inference variables’, such as those relating to the beliefs and psychological states of the person; gambling and games, however, are ‘low-inference variables’, easy to assess by the ethnographer.

Despite these and other objections, cross-cultural statistical studies have a small but dedicated following, especially in the USA. The conversion of ethnographic databases into easily accessible electronic format, together with the possibility that anyone with a personal computer can run statistical tests on these databases, has in the last decade infused fresh life into this research tradition. Cross-cultural studies have undoubtedly yielded interesting and important results that would have been hard to arrive at using other methods.

There seems to be only one published cross-cultural study that concerns gambling specifically, the aforementioned study by the economist Frederic Pryor (1976), data from which are presented in Figure 2. The objective of that study was to validate the Friedman– Savage utility function (Friedman and Savage, 1948); the survey is thus focused on economic factors, being part of an ambitious project titled The Origins of the Economy (Pryor, 1977). Pryor claims that the ideas underlying the utility function proposed by Milton Friedman and Leonard Savage‘. . . can permit us to make accurate predictions about which pre-capitalist societies do and which do not engage in gambling’. The study employs a ‘simple multivariate least-squares regression analysis’ and is based, as mentioned, on a custom sample of 60 societies derived from the World Ethnographic Sample (Murdock, 1957). Pryor’s final regression model, including four independent variables—‘location in North America’, ‘presence of domestic commercial money’, ‘presence of socio-economic inequality’, and ‘society nomadic or seminomadic and more than half of its food supply coming from animal husbandry’— explains 68% of the observed variation in the presence and intensity of gambling (r2=0.68). The model thus has a good prediction capacity.

There are, however, several cross-cultural studies not concerning gambling, per se, but games more generally (for an overview, see Chick, 1984). The seminal study is ‘Games in culture’, published in 1959 by John Roberts, Malcolm Arth, and Robert Bush. The authors proposed a trichotomy of games: games of physical skill, strategy, and chance, examples being soccer, chess, and roulette, respectively. Games of physical skill, according to their definition (p. 597), may or may not involve chance; games of strategy do not involve physical skill but may or may not involve chance; in games of chance, both physical skill and strategy should be absent. This early survey used a custom sample of 50 non-Western cultures.

This study has been followed by several others using the same typology. The Ethnographic Atlas, as well as its various subsets such as the widely used Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (Murdock and White, 1969), includes pre-coded variables for games following this classification (for a description of the main ethnographic samples, see Ember and Ember, 1998, pp. 659–63). In these studies, two themes are discussed recurrently. The first is the eventual association between -

Figure 2. Prevalence of gambling in 60 pre‐capitalist societies (source data: Pryor, 1976)

- levels of societal complexity and the three types of games (Ball, 1972, 1974; Chick, 1998; Roberts etal., 1959; Silver, 1978; Sutton-Smith and Roberts, 1970). Within this theme, the evolution of games in history is also discussed. We will return to these issues in the following section of the paper.

The other prominent theme in this literature is the relation between games and infant socialisation (Barry and Roberts, 1972; Roberts and Sutton-Smith, 1962, 1966; Roberts etal., 1959, 1963; Sutton-Smith and Roberts, 1964, 1970; Sutton-Smith etal., 1963). The basic notion is the ‘conflict-enculturation hypothesis’, which suggests that‘. . . conflicts induced by child training processes and subsequent learning lead to involvement in games and other expressive models’ (Roberts and Sutton-Smith, 1966, p. 131). Certain childhood experiences would thus predispose an adult to prefer one type of game over another. The value that one would attach to the results of these surveys depends on whether or not one accepts the psychoanalytical or psychodynamic assumptions upon which they rest. Studies focused on this theme have been pursued almost exclusively by John Roberts and Brian Sutton-Smith and have met with little response from other scholars. Appearing as a highly questionable and dead-end trail of research, they will not be further discussed here (for a critique and statistical re-examination, see Townshend, 1980).

The cross-cultural investigations based on Roberts’ etal. trichotomy of game types do not identify gambling as a discrete phenomenon. In the predominantly non-Western cultures of the various samples used, however, ‘games of chance’ are in most cases likely to have involved the staking of valuables or money; in general, such games become engaging for adults only when there are stakes (cf. DeBoer, 2001, p. 237). While ‘games of chance’ in principle include many games played by children, most games of chance reported in the ethnographies, from which the cross-cultural samples draw their data, are those played by adults (Roberts etal., 1959, p. 597). Pryor (1976, p. 826), who coded 60 cultures from a custom sample of societies for the presence and intensity of gambling, compared his coding with that for the presence of ‘games of chance’ in one of the standard cross-cultural samples (the Ethnographic Atlas, as of 1972) and found that in the 43 cases in which the coding could be compared, there was an 86% agreement between ‘games of chance’ and ‘gambling’, with no systematic bias in the error pattern. Taken with a measure of caution, these studies may thus tell us something about the distribution of gambling.

The following section includes a critical examination of statements that have been made in cross-cultural studies regarding factors that affect the distribution of gambling and games of chance.

Factors Promoting or Restraining Gambling Presence of Commercial Money

Pryor (1976) found that gambling correlates positively with the ‘presence of domestic commercial money’. This association seems primarily to indicate that gambling is facilitated by the presence of a generally accepted measure of value. Among the Pawnee Indians in the nineteenth century, betting on the ‘hand game’ was described as follows (Culin, 1907, p. 276, citing G. Bird Grinell): ‘The wagers are laid—after more or less discussion and bargaining as to the relative value of things as unlike as an otter-skin quiver on one side and two plugs of tobacco, a yard of cloth, and seven cartridges on the other. ..’

Placing wagers of money rather than items of various kinds and values would, of course, have been easier for the Pawnee. It is not self-evident, however, that the introduction of money among a people who are already gambling will lead to increased gambling simply because it will be easier to bet. In some societies, where there is no commercial economy or where there are economic spheres with goods that are not readily converted into money, gambling can serve as a means of circulating valuables so that they become more evenly or strategically distributed, from the point of view of the group as a subsistence unit (Binde, forthcoming; Wagner, 1998).

For instance, the anthropologist James Woodburn (1982) has found that among the Hadza of Tanzania, an egalitarian people subsisting on hunting and gathering, gambling prevents the individual accumulation of metal-headed hunting arrows, knives, axes, and beads. Woodburn concludes (p. 444) that ‘it is paradoxical that a game based on a desire to win and, in a sense, to accumulate should operate so directly against the possibility of systematic accumulation. Its levelling effect is very powerful’. A similar argument has been proposed concerning the gambling of modern Australian aborigines (Goodale, 1987). The gambling games of the Canadian Inuit serve to convert value between the separate economic spheres of rifle cartridges, indispensable for hunting, and cash (Riches, 1975), and have also been interpreted as contributing to survival in the precarious arctic environment by redistributing scarce resources and implements (Glassford, 1970).

Hence, an important social and economic consequence of gambling, which can be assumed to contribute to its continuity as a social practice in some societies, is that valuables other than money are circulated. Valuables rather than cash may be more in accord with indigenous gambling customs for other reasons as well. For instance, bets placed at the Zuñi footraces consisted of all kinds of valuables and useful objects. These were placed in a large heap, which was a focus of attention; bettors gathered around it admiring this treasure of wealth (Hodge, 1890). The heap of valuable objects, associated with all kinds of enjoyments and pleasures, is a symbolic cornucopia that bills and coins cannot fully replace. Similarly, the bets placed at important lacrosse matches by North American Indians, consisting of valuable and attractive objects, were displayed on mats spread out on the ground. The bet of each person was tied together by means of a string with the bets of another person betting on the opposing team, to prevent the bets becoming mixed up (Vennum, 1994). Since the bundles of bets were an ostentatious display of wealth as well as metaphor for the warlike nature of this often very violent game—tribe fighting tribe in a battle that often was fought man-against-man—the appeal of lacrosse waned as bets of money replaced bets of goods (Vennum, 1994, p. 109). The introduction of commercial money thus ‘disenchants’ gambling, loosening its ties to a traditional symbolic and ceremonial domain (cf. Simmel, 1978 [1900]).

While there are cultures where bets of money are more or less discordant with traditional gambling practices, there are cultures where the opposite is the case; conceptions of items of value are incompatible with gambling and thus prevent their use for that purpose. In Melanesia and much of Micronesia and Polynesia, valuables, food, and useful objects—such as shells, pigs, yams, and stone axe blades—were exchanged according to elaborate systems that constituted the backbone of social organisation (e.g. Malinowski, 1922; Mauss, 1990 [1925]; Weiner, 1976). A basket of food may thus signify social obligations and rights to land use and a string of shells may symbolise a person’s position within a social network or hierarchy. Gambling, which to a considerable extent brings about a random distribution of goods, appears as fundamentally alien to these cultural systems. This can be compared to a gambler in a Western country betting with his or her wedding ring or collection of medals and cups won at athletic sports. Such things have occurred, but are regarded as desperate acts by a compulsive gambler. Therefore, gambling starts to be practiced in societies with extensive exchange systems only when money, belonging to a commercial rather than traditional economic sphere, comes into use, such as in New Guinea in the second half of the twentieth century (Brandewie, 1967; Hayano, 1989; Maclean, 1984; Mitchell, 1988; Sexton, 1987; Zimmer, 1986). In societies in transition from traditional to modern, gambling may serve to complement traditional exchange systems—not suited to handle substantial sums of money originating from external sources, such as wages from labour outside the village—by distributing cash (Maclean, 1984; Mitchell, 1988; Zimmer, 1986).

To sum up, indigenous gambling using wagers of valuables might lose some of its social and symbolic significance with the introduction of commercial money, but people can nevertheless continue to gamble in more ‘modern’ ways. In many other cultures, the social significance of valuable items has traditionally restrained gambling, even making it virtually impossible, and the introduction of money is a prerequisite for adopting the practice of gambling. Thus, Pryor’s (1976) conclusion that the use of commercial money is positively associated with the presence and intensity of gambling appears to be well founded.

Societal Complexity

As mentioned, the relationship between types of games and the complexity of societies has been investigated in several cross-cultural studies (Ball, 1972, 1974; Chick, 1998; Lenski, 1970; Roberts etal., 1959; Silver, 1978). It has been suggested that the more complex a society, regardless of how complexity is measured (see Chick, 1997; Freeman and Winch, 1957), the more likely it is that games of strategy are present (Townshend, 1980). For instance, Chick (1998) found that in a subset of the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, not one single society lacking multicommunity organisation had games of strategy, and Roberts et al., (1963) observed that among 32 tribes where games of strategy were present, metal working (an indicator of technological advancement and societal complexity) was present in 31 and lacking only in one.

The probable reason for the association between games of strategy and societal complexity is that games often are modelled after patterns of interaction in the social world; the more complex and varied this world is, the more likely it is that games will be invented and played that predominantly involve strategy. The game of Monopoly, for instance, could hardly have been invented, or make much sense for players, in a society lacking a market economy. Since the complexity of society is assumed to increase over historical time, this observation has implications for theories concerning the evolution of games. Among those working out such theories, there is agreement that games of strategy come late in the evolutionary sequence, but disagreement as to whether games of chance or games of physical skill came first (Chick, 1997, 1998; Roberts and Barry, 1976; Roberts and Sutton- Smith, 1966; Roberts etal., 1963).

As for the relationship between games of chance and societal complexity, some cross-cultural studies state that there is no such relationship (Chick, 1998; Sutton- Smith and Roberts, 1970) while others suggest some sort of relationship (Ball, 1972, 1974; Silver, 1978). Concerning gambling, rather than games of chance, Pryor (1976) found a significant correlation between the presence of gambling and higher levels of economic development, which is an indicator of societal complexity (see also Price, 1972). Chick (1997), after reviewing common measurements of societal and cultural complexity, concludes that a simple yet useful measure is the (logarithm of the) largest settlement size in a society. A look at Figure 1 suggests that gambling is positively associated with societies with big settlements; in areas where there was little or no gambling, such as in Melanesia, Australia and much of South America, there were few societies where the size of the largest settlement exceeded 1,000 inhabitants. Large settlements, on the other hand, were common in many of the societies where there was gambling (with the exception of most North American tribes). In the cross-cultural tabulations executed by Robert Textor (1967, FC 459) we may note that among the 127 cultures coded with respect to the eventual presence of games of chance, as well as of the eventual presence of a city, all of the 65 cultures lacking games of chance also lack cities; in 49 of these cultures the average community size is smaller than 200 inhabitants.

Thus, gambling seems to be associated with societal complexity, and we may ask why. One possibility is that societal complexity in itself has no impact, but rather some other covarying factor(s); for instance, the presence of commercial money, the type(s) of subsistence economy, or the extent of social stratification (see below). Another possibility is that societal complexity, in the sense of a variety of social environments with particular cultural codes, in itself promotes gambling. There is no doubt that the more complex a society, the more varied is its repertoire of games (Ball, 1972; Silver, 1978). It is also clear that certain economic, social, and ideational configurations are, for a variety of reasons, some of which are discussed in this paper, more compatible with gambling than others. In a society with low complexity, such configurations are few in number, and perhaps there is a greater probability that there is no configuration in which gambling fits well. In a large-scale society—integrating a plurality of social classes, regions with varying economic characteristics, and groups of people with different religion and worldview—there is a greater probability that there is at least one such configuration compatible with gambling.

Type of Social and Economic System

Pryor’s (1976) study is intended, as mentioned, as a cross-cultural test of the Friedman– Savage utility function. This function elaborates upon expected utility theory; while economists formerly held that the marginal utility of increasing wealth is uniformly decreasing (Bernoulli, 1954 [1738]), Friedman and Savage (1948) argued that utility, in a certain segment of wealth, is increasing. Thus in that segment, the expected value of each additional unit of wealth is worth more than the preceding unit, and the otherwise concave utility function has a convex segment. The reason for this is, according to Friedman and Savage, ambition for social advancement; persons who are close to moving to a higher social class are eager to do so, and the perceived value of the units of wealth that would allow this is therefore comparatively high. Previously, expected utility theory had not been able to explain why people gambled; even with a 100% return on bets this appeared as irrational, since a unit of wealth won always ought to be worth less than a unit bet. Within the paradigm of ‘economic man’ (Edwards, 1954), the Friedman–Savage utility function explains gambling and purchase of lottery tickets; people wish to win the extra money that would allow them to move to a higher social class. The cost of the lottery ticket is worth its price since it confers this possibility.

A number of empirical studies of gambling behaviour have supported the Friedman– Savage theory (Brunk, 1981; Downes etal., 1976, pp. 91–95, 105; Tec, 1964;Weitzman, 1965), but it has also been criticised by economists who claim that gambling should be explained by various other modifications of the basic utility function (e.g. Markowitz, 1952; Ng, 1965). Today, the Friedman–Savage theory appears somewhat outdated with respect to its implications for gambling. The theory has an intuitive appeal and is certainly of some relevance (cf. Haruvy etal., 2001), but the propensity to gamble is, from an economic perspective, better explained by admitting that gambling has a utility value in itself, such as excitement, entertainment, and the buying of a dream of wealth and prosperity (Bailey et al., 1980; Bird etal., 1987; Busche and Hall, 1988; Forrest etal., 2002; Hamid etal., 1996; Hirshleifer, 1966; Marfels, 2001; Miyazaki etal., 1999; Thaler and Ziemba, 1988; Wagenaar etal., 1984; Walker, 1998; Woodland and Woodland, 1999).

In his study, Pryor (1976) found that gambling is positively associated with ‘presence of socio-economic inequality’ (as measured on a five-point scale from ‘little or no’ to ‘considerable’). His claim that this musters support for the Friedman–Savage utility function is, however, doubtful. The Friedman–Savage utility function predicts that persons belonging to the upper strata of a lower class derive most utility from gambling, and therefore act economically rationally when they gamble; about this, Pryor’s study gives no direct evidence.

What is suggested by the association between gambling and social inequality is probably something more general. Let us imagine a society where there are poor and rich. The rich have plenty of food and conveniences and live a pleasant life; the poor suffer from hunger, live in misery, and must work hard. What is more natural than the poor wishing to become rich? Among the poor we must assume there to be many persons who try out every conceivable way of becoming rich or at least better off. Gambling provides a shortcut to wealth and a better life, and although few actually are able to use it successfully, its very existence inspires hope and dreams of a better life. Individuals partake in gambling for many reasons—for instance as an intellectual challenge at games requiring skill, to test their luck, for the excitement of risking and winning, to conspicuously show possession of wealth—and the dream of becoming rich is one of these reasons. This dream is born of socio-economic inequality and we should therefore expect gambling to be more common and intense in societies with high compared to low social inequality. In economic terms, gambling has a greater utility in itself in such societies.

Another variable that emerged as significantly but negatively associated with gambling in Pryor’s study was, ‘society nomadic or semi-nomadic and more than half of its food supply coming from animal husbandry’. Gambling is less common in these societies than it is in others. Pryor’s explanation is that gambling has a comparatively high disutility under such economic circumstances. He argues that the wellbeing of a nomadic herder depends to a great extent on keeping the size of the herd above a certain critical level. The flock must be able to reproduce and maintain its size despite animals being slaughtered for food and being lost through droughts, pests, raiding, attacks by predators, and so on. Below this level, animals should not be slaughtered but left to reproduce. Maintaining an unusually large herd also constitutes a problem; it is difficult to herd and may exhaust the pastures.

Pryor’s argument would explain why animals are not staked in gambling by herders, but it does not say much about gambling for other stakes. However, the loss of such stakes (excluding money and precious metals) is also likely to have a high disutility. The amount of belongings that the nomadic family can bring with it is restrained by practical limits; everything must be carried on the back or loaded on pack animals. Most belongings are thus indispensables; besides those, only a few ‘luxury’ items not necessary for survival can be transported. There are therefore not many items that the nomadic herder can readily dispense with. Furthermore, a windfall of additional belongings creates a problem. The herder already owns all the indispensable items needed, so there is no point carrying any more of these, and there is a limit to the volume of ‘luxury’ objects that the family can transport. Only the use of money for gambling solves these troubles.

Hence, the nomadic herder who loses heavily by gambling is in greater trouble than a peasant, and the one who wins a lot is not as happy. Again, this has nothing to do with the particular shape of the Friedman–Savage utility function; rather the contrary. The Friedman–Savage utility function primarily describes the utility of wealth in capitalist economies, where there are things such as general purpose money, monthly income, and goods for sale on a competitive market. The utility function in a nomadic society might look very different, and it is precisely this that Pryor’s data suggest. In nomadic societies, there is a threshold level of wealth below which it is dangerous to go; consequently, loss of wealth has a very high disutility in this segment of the function. Furthermore, for practical reasons, the marginal utility of wealth ought to be more rapidly decreasing than in industrial and agricultural societies.

Risk and Uncertainty

Under the heading of ‘Gambling’ in the Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics (Paton, 1913), we find the following musing on the geographical distribution of gambling:

Generally speaking, it may be said that gambling has its chief hold on races which exist by hunting, and also on the pastoral, military, and mercantile types of culture. These modes of life are by nature less stable, and seem to generate a craving for sudden and exciting reveals of fortune, without which life seems colourless. The peasants, on the other hand, who have to work hard and steadily for their sustenance, are comparatively free from the habit.

A similar suggestion, based on cross-cultural research, is that games of chance are more common ‘. . . in the presence of environmental, individual and social uncertainty regardless of the relative complexity of the cultures in which they occur’ (Ball, 1974; see also Roberts and Sutton-Smith, 1966; Sutton-Smith and Roberts, 1970, p. 102). The argument here is that, since games are modelled after the life-world, a high degree of uncertainty would imply a greater probability of the presence of games of chance: ‘in societies where men have little control over, or understanding of, the forces that shape their lives, the games they invent are usually games of chance’ (Lenski, 1970, p. 135).

This argument is a compound of several suggestions, all of which are problematic. ‘Environmental uncertainty’ evidently refers to an ‘objective’ assessment of the environment in case. This, however, tells little of how the environment is perceived by the people who live in it. The Inuit, the Indians of the Tierra del Fuego, the Australian Aborigines, the Mongolian nomads, and a host of other peoples around the world show us that even the harshest environment, with rapid and unpredictable shifts between weather conditions, can be turned into a relatively secure life-world and experienced as such. Furthermore, a great many peoples in such environments have no games of chance (Price, 1972; Reefe, 1987, p. 47). ‘Individual and social’ uncertainty is equally problematic. In the cross cultural studies discussed, there have been few attempts to measure directly the perceived ‘uncertainty’ of individuals in the cultures in question, which is typically inferred from social and cultural features viewed in the light of various psychological theories.

Thus, the cross-cultural studies that claim to find a relationship between games of chance on the one hand and risk and uncertainty on the other should be taken with a liberal pinch of salt. Pryor’s cross-cultural study (1976), which concerned gambling rather than games of chance, found no correlation between ‘hardness of environment’ and gambling.

From a theoretical point of view, we would expect gambling, especially with high stakes, to be stimulated in societies and among groups of people where individual risk-taking is culturally construed as a positive character trait. Such a cultural value, however, has little to do with the natural environment but rather with features of social organisation, such as the presence of intra- and inter-tribal warfare and violence, requiring brave warriors, or an emphasis on entrepreneurship and economic competition between individuals. As to the individual experience of life as risky and exciting as compared to secure and dull, we should expect that the perception of comparative security, predictability, and routine of life would stimulate a pursuit of sensation, excitement and action, all of which can be experienced in gambling and many other leisure activities (e.g. Abt etal., 1985; Bloch, 1951; Boyd, 1976; Elias and Dunning, 1970; Goffman, 1969; Zuckerman, 1994).

Religion and BeliefSystems

In the seminal study by Roberts etal., (1959), it is suggested that games of chance are related to religious beliefs. The presence and absence of games of chance are cross-tabulated with the ‘frequency of benevolence and aggression by gods’ and the ‘frequency of coercion of gods and spirits’, as this was coded in a previous study (Lambert etal., 1959) in two small samples of non-Western cultures (n = 18 and 15). The result of the survey is that games of chance tend to occur more frequently in cultures where the gods or spirits are believed to be benevolent and easy to coerce, while such games are less common in cultures where gods and spirits are perceived as aggressive and hard to coerce.

At first glance, this relationship makes sense. In many traditional non-Western cultures, there is no conception of probability in a mathematical sense; phenomena governed by chance are often believed to be manifestations of fate or the will of supernatural beings (Lévy-Bruhl, 1924). Hence, if such beings were malevolent most of the time, the gambler would consider his prospects of winning at games of chance to be small, but if they were mostly benevolent and receptive to prayers and requests, the gambler would presumably regard his chances of winning more optimistically. Benevolent gods help the gambler while evilminded ones use their influence to thwart his efforts. We are reminded of the old Christian imagery of the devil guiding the fall of dice with the intention to maximise frustration, unhappiness, and discord among gamblers. On a societal level these attitudes would in the first case promote and in the second case inhibit the presence of games of chance. This reasoning assumes, of course, that the prospective gambler has a subjective view and does not reason that things are equally good/bad for all players.

Unfortunately, there has been no attempt to replicate this finding. The study has two major weaknesses. The first is the small sample of exclusively non-Western cultures. The second is the reliability of the coding for ‘frequency of benevolence and aggression by gods’. This is a ‘high-inference variable’ that is difficult to assess by the ethnographer in the field and problematic to code and scale (cf. Spiro and D’Andrade, 1958); apparent variables, such as the ‘presence of commercial money’, are much easier to handle. Furthermore, a look at the list of the cultures in the sample, in which the gods are perceived as aggressive rather than benevolent, gives the impression of societies that more than others are characterised by social hierarchy, rigidity of norms, taboos, and frequent punishment for wrongdoing (see also Textor, 1967, FC 425). Perhaps the pervasiveness in social life of moral rigidity and conformity to norms gives rise to a conception of the gods as evil and unforgiving as well as having an inhibiting function on gambling, which is an activity that by its random distribution of wealth has the potential to disturb the socio-economic order.

In The Origins of the Economy, Frederic Pryor (1977, p. 265) mentions that he found a correlation between the absence of gambling and the presence of ‘economic witchcraft’; that is, a belief in witchcraft directed against ‘a person’s crops, herd, or hunting, fishing or gathering luck’. He suggests that this is because any winner would fear the malevolent witchcraft of a disgruntled loser; winning would not be enjoyable and therefore there is no or little gambling. We are not informed of any details on this statistical correlation and it is therefore difficult to judge the plausibility of Pryor’s suggestion. It appears, however, a bit unconvincing since witchcraft suspicions and accusations within local communities typically are directed towards socially deviant persons or used as a weapon in factional disputes (Douglas, 1970) and do not usually target someone who has happened to displease someone else on a single occasion. Ethnographic examples of persons who refrain from gambling, stating that they do this for fear of a loser’s witchcraft, would make Pryor’s suggestion more plausible, but such reports do not seem to be found in the ethnographic literature. If there is indeed a statistical correlation, it may be illusory and explained by a third factor which could be, as in the case with benevolent and malevolent gods, a rigid and prohibiting system of norms that tend to restrain gambling as well as give rise to beliefs in the malevolent witchcraft of others.

Gambling and religion are often assumed to be in inherent opposition. Gambling is thought of as a purely secular activity spurred by the possessive instinct, while religion is assumed to be concerned with the spiritual and otherworldly. Perhaps there would therefore be a negative association between religion and gambling? This is not the case, however, because there is no such simple relationship between gambling and religion.

Gambling and religion are two spheres of beliefs and activities that seldom have an indifferent relationship; usually there is either a state of concord or of conflict (Binde, 2003). Many indigenous religions, as well as some ‘popular’ and local interpretations of world religions, coexist in harmony with gambling; religious rituals involve gambling, myths tell about gambling gods, gambling is invested with religious and magical significances, and so on. Gambling and religion go well together because there is a common preoccupation with the unknown, mystery, fate, destiny, despair and happiness, receiving something valuable from ‘higher powers’, and the hope for a transformed and better life. Monotheistic world religions, however, claim a monopoly in such matters and tend to criticise gambling. Several authors have suggested that religious denunciation of gambling is in part due to a conception that gambling competes with religion (Binde, 2003; Brenner and Brenner, 1990; Fuller, 1974; Reefe, 1987; Sutton-Smith, 1997).

If gambling occurs in a monotheistic society—and this is likely, since monotheism is a cultural feature associated with high societal complexity, and thereby also the presence of commercial money and social inequality—it is hence bound to be criticised, restricted or outlawed. It might be noted that Islam, which is the most consequential in its monotheism among the world religions, is also the one that most consistently has condemned and outlawed gambling (Rosenthal, 1975). Criticism and prohibition does not necessarily mean, however, that gambling ceases to be practiced. History shows that gambling under such circumstances usually continues to be practiced illegally and only heavy moral pressure or the strict enforcement of anti-gambling laws will eradicate it.

Among the socio-cultural conditions that give rise to monotheism are some of those which also favour the presence of gambling and since there is an inherent conflict between such religion and gambling, the resulting state is difficult to predict. The extent to which gambling will be tolerated seems to depend on certain societal factors, such as the role of religion in forms of government and historical circumstances unique to a particular society and a certain period.

‘Cultural Diffusion’and Contiguous Areas of Gambling and Nongambling

Although Figure 1 is an overview, lacking in detail regarding particular tribes and small-scale societies, it appears that societies with indigenous gambling tend to cluster in geographical space and form a few large areas (cf. Kroeber, 1948, p. 553; Price, 1972, p. 162; Reefe, 1987, p. 47): (1) North America, (2) Europe, (3) western-central Africa, and (4) China and mainland Southeast Asia. Areas where there was little or no gambling are: (1) South America, (2) southeastern Africa, (3) northern Asia, and (4) Melanesia, Australia, and New Zealand.

In part, this distribution of gambling can be explained by similarities among the societies of the various areas. For instance, before contact with the West, the Australian continent was inhabited exclusively by hunter–gatherers with totemic social organisation. However, there are some areas for which such explanations do not suffice; most notably North America, where there were a wide variety of societal types, including nomadic as well as sedentary, foraging as well as horticultural, and egalitarian as well as strictly hierarchical. In Pryor’s study (1976), the most significant correlation found was that between gambling and ‘location in North America’, which Pryor attributes mainly to ‘some sort of diffusion phenomenon which remains to be explained’ (p. 829).

With regard to gambling and the phenomenon of cultural diffusion, the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber noted (1948, p. 553):

The areas of gambling and nongambling are both, on the whole, rather large and compact. We must therefore conclude that they are both due to consistent diffusions. What is of interest in this matter of gambling is that these seem to have been diffusions of attitudes as such, or of failures of interest to develop, rather than ordinary diffusions of culture content such as specific games or devices.

The diffusion of ‘specific games’ that Kroeber refers to was earlier an issue of debate among anthropologists (for a summary, see Avendon and Sutton-Smith, 1971, p. 61f). Some saw the presence of similar games in different cultures as evidence of diffusion and cultural contact (e.g. Tylor, 1880), while others stressed the possibility of similar games being invented independently (Erasmus, 1950). As to gambling devices, these have evidently spread among societies, as have many other implements and tools. For instance, the various forms of North American Indian ball play, in which balls and clubs are used, most probably had their origin in Mesoamerica (Eaglesmith, 1976).

The spread of gambling is, as Kroeber notes, a different thing from the spread of specific games and gaming implements. Gambling is both a social and an economic activity, and it may fit more or less well with the socio-economic system of a particular society as well as with its accompanying moral system (Binde, forthcoming). In determining this ‘fit’, there might not only be ‘internal’ factors, some of which have been discussed here; there might also be ‘external’ factors pertaining to regional systems in which groups of people and tribes relate to each other. Such systems might involve hostility, such as feuding and war, or be constituted by leagues and federations.

My theory is that the remarkable prevalence and intensity of North American Indian gambling can be explained by its inter-tribal nature. Although gambling took place between individuals, between clans, and between villages, the most spectacular gambling events— with the highest bets, the most people involved, and the most excitement—were those involving different tribes (DeBoer, 2001). In the big lacrosse games, for instance, one tribe challenged another (or a village belonging to one tribe challenged a village belonging to another tribe) to a game with hundreds of players, which as a rule was violent, resulting in bloodshed, broken limbs, and players being knocked unconscious (Vennum, 1994). Betting was ubiquitous and involved, as mentioned, loads of valuables. Everyone bet, of course, on their own team and the members of the winning tribe won everything staked by those of the opposing tribe. The affinity between lacrosse and war is evident and expressed by a multitude of metaphors and parallels; for instance, by the game being called the ‘little brother of war’ (Vennum, 1994, Chapter 13). Intertribal gambling was not confined to betting on ‘sport events’. It was also widespread in pure gambling games, such as the hand game, the stick game, and the moccasin game, and in these games as well metaphors of war were common (DeBoer, 2001). The ethnographic literature abounds with descriptions of how one village or tribe challenged another; betting went to the extreme, and the game resulted in one of the parties being stripped of wealth (a particularly suggestive example is found in Culin, 1907, pp. 250–52).

Honour and prestige were highly regarded values among virtually all North American tribes. Individuals, clans and tribes were jealous of their good name and ready to protect it at high cost. Honour was valued higher than material belongings and the motto ‘better die in honour than live in disgrace’ was not empty words. A challenge to a gambling ‘battle’ was therefore hard to refuse; the one who did not accept it was regarded as a coward and lost considerably in prestige.

Now, assume that an ethos connecting gambling with contestation and affirmation of prestige had been established in one particular tribe and encompassed gambling between individuals and villages. If the tribe as a whole challenged another tribe to gamble, this could hardly be refused. The two tribes gambled, and the notion of gambling as a challenge of honour thereby spread to the other tribe. And so it continued—gambling spread from tribe to tribe. Gambling served as a substitute for feuding and war; tribes could oppose each other without the devastating consequences of armed confrontation. Just as the Potlatch feasts on the northwest coast, in which clans and tribes tried to outdo each other in arranging the most lavish feast, were ‘fights with property’ (Codere, 1950), gambling was a war with valuables in which complex relationships of conflicts and alliances on different levels of tribal organisation could be acted out. Gambling was sustained at a level of high intensity because it had this important inter-tribal function and relied on a cultural feature that all tribes had in common—the sense of honour. Gambling became so important in inter-tribal contacts and confrontations that few tribes could refrain from adopting the practice. This, I believe, is the solution to the riddle as to why gambling was so widespread and intense among the North American Indians.

A question that may be asked regarding the cultural diffusion of games is how gambling spread from Western societies to traditional non-European societies. Contact with the West has brought gambling to many peoples who did not originally gamble, such as the Australian aborigines and many New Guinean peoples. This might lead us to believe that a formerly non-gambling people begins to gamble because they have observed the gambling habits of Westerners, and take these up as they find them intriguing or entertaining. However, Pryor (1976), in his cross-cultural study, tested a ‘contact-with-the-West’ variable, but it failed to correlate significantly with gambling in the regression analysis. Thus, it appears that it is the economic and social changes that contact with the West brings with it—such as increased social inequality and the use of commercial money—that turn a non-gambling people into gamblers. This is a subject that would be illuminated by the comparison of case studies of indigenous peoples in the process of adopting gambling. Another subject that requires further investigation is how gambling has spread through earlier waves of colonisation, both in the West and the East, and along trade routes.

Concluding Discussion

The rough picture that emerges in this paper of the distribution of indigenous gambling could certainly be improved by a closer scrutiny of historical records and ethnographic sources. Although this preliminary investigation has been concerned mainly with gambling in the past, its approach has been essentially ahistorical, collapsing different moments and periods in chronological time into the concept of a time before much contact with the West. This has the advantage of facilitating the observation of general patterns in the distribution of indigenous gambling and of the factors that promote and restrain the practice of gambling. To draw a picture of the history of world gambling—delineating the extent to which gambling has evolved independently in different areas of the world and how it has spread from culture to culture—would require a genuinely historical approach. At least with respect to more recent times and regions of the world for which there are sufficient historical sources, such diachronic studies are possible and would throw further light upon the issues discussed in this paper.

Extensive ethnographic and historical evidence strongly suggests that gambling is not a universal phenomenon and that there is no specific ‘gambling instinct’; gambling does not fulfil any individual or social need that cannot be fulfilled in other ways. Gambling is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon, a remarkably flexible way of redistributing wealth, which is embedded in the socio-cultural systems of societies, constituting, for example: a leveller of differences in wealth in egalitarian communities, an arena for individuals to achieve and contest prestige in hierarchical social environments, and a multifaceted leisure product in modern commercial societies (Binde, forthcoming). Since socio-economic systems are supported by ideologies concerning the proper distribution of wealth, gambling may be conceived of as reprehensible or commendable, or something inherently ambiguous in moral terms. Games of chance are associated with notions of fate, destiny and the unknown, and they may exist in concord with religion or, when established religion claims a monopoly in such matters, be severely in conflict with it (Binde, 2003). Thus, there are many factors that have an impact on gambling and these do not remain stable over time. History shows that attitudes towards gambling may change rapidly, oscillating between periods of harsh condemnation and periods of ‘gambling mania’ affecting all social strata (Rose, 2003).

Despite this variation and complexity, there are a number of general factors that promote or restrain gambling at the societal level. Frederic Pryor’s (1976) cross-cultural study of gambling shows that the presence of commercial money and social inequality promotes gambling, while gambling tends to be rare in nomadic societies relying heavily on animal husbandry. This latter negative association can be interpreted as resulting from a particularly high disutility of substantial gambling losses as well as a low utility of substantial gambling winnings. It remains to be investigated whether similarly shaped utility functions restrain gambling also in other types of societies and whether there are other types of utility functions, formed by certain subsistence patterns, that have a significant impact on the practice of gambling.

Furthermore, there is an association between societal complexity and gambling— expressed, for instance, by the co-variation of presence of cities and the presence of gambling—that might be explained not only by societies with large settlement size tending to have commercial money and considerable social inequality, but also by their having a plurality of socio-cultural environments, which increases the likelihood of at least some of them favouring gambling.

Polytheistic and ‘animistic’ religions tend to exist in concord with indigenous gambling while monotheistic religions tend to denounce it (Binde, 2003). This means that indigenous religions seldom restrict gambling — rather on the contrary, these religions may encourage gambling — while, monotheistic religions under certain conditions do so. It would require further analyses to find out under which socio-cultural conditions monotheistic religions intensely condemn gambling and why those in political power use religion as an ideological basis for the suppression of gambling. There is no strong evidence that other factors relating to religion and worldview have a systematic impact on the presence of gambling in a society; a scrutiny of Figure 1 of the distribution of indigenous gambling does not inspire any new hypotheses concerning this.

The role of gambling in inter-tribal and inter-community relationships needs to be investigated further. This would lead to a better understanding of ‘diffusion’ phenomena; that is, that gambling and non-gambling societies tend to cluster in certain regions of the world. I have proposed that the high intensity of gambling among the North American Indians is explained by their gambling having a warlike quality, dense with notions of competition and prestige, that had great significance in contesting and maintaining relationships between clans and tribes.

Because of the fundamental problem to define, quantify and compare cultural and social phenomena pertaining to different societies, together with a number of more specific methodological difficulties, the result of cross-cultural studies should always be viewed with a certain amount of caution. This article has discussed results of such studies from the perspective of social anthropology and in the light of ethnographic information from particular societies. Some of these results have appeared questionable, others credible, and still others have been found to have additional dimensions, the exploration of which leads us to greater insight into gambling as cultural and social phenomena. To conclude, cross-cultural studies, if read with their inherent shortcomings in mind, do teach us something about why some societies have historically practiced gambling while others did not.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based has been financed by the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation. An early version of the paper was presented at the Fifth European Conference on Gambling Studies and Policy Issues, Barcelona, 2002. Thanks to Professor Åsa Boholm and Ralph Heiefort, both at Göteborg University, and the two anonymous reviewers at the International Gambling Studies for many valuable comments.

References

Abt, V., Smith, J.F. and Christiansen, E.M., 1985. The Business of Risk. Commercial Gambling in Mainstream America, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KA.

Alegria, R.E., 1951. ‘The ball game played by the aborigines of the Antilles’, American Antiquity, 16(4), pp. 348-52.

Avendon, E.M. and Sutton-Smith, B., 1971. The Study of Games, Wiley, New York.

Bailey, M.J., Olson, M. and Wonnacott, P., 1980. ‘The marginal utility of income does not increase: Borrowing, lending, and Friedman-Savage gambles’, American Economic Review, 70(3), pp. 37279.

Ball, D.W., 1972. ‘The scaling of gaming: Skill, strategy and chance’, Pacific Sociological Review, 15, pp. 277-94.

Ball, D.W., 1974. ‘Control versus complexity: Continuities in the scaling of gambling’, Pacific Sociological Review, 17(2), pp. 167-84.

Bankoff, G., 1991. ‘Redefining criminality: Gambling and financial expediency in the colonial Philippines, 1764-1898’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 22(2), pp. 267-81.

Barry, H., III. and Roberts, J.M., 1972. ‘Infant socialization and games of chance’, Ethnology, 11, pp. 296-308.

Berndt, R.M. and Berndt, C.H., 1947. ‘Card games among aborigines of the Northern Territory’, Oceania, 17, pp. 248-69.

Bernoulli, D., 1954. ‘Exposition of a new theory of the measurement of risk’ (translation, originally published in 1738), Econometrica, 22(1), pp. 23-36.

Binde, P., 2003. ‘Gambling and religion: Histories of concord and conflict.’ Paper presented at the 12th International Conference on Gambling & Risk-Taking, May 26-30, 2003, Vancouver.

Binde, P., forthcoming, ‘Gambling, exchange systems, and moralities’, Journal of Gambling Studies.

Bird, R., McCrae, M. and Beggs, J., 1987. ‘Are gamblers really risk takers?’ Australian Economic Papers, 26(49), pp. 237- 53.

Bloch, H.A., 1951. ‘The sociology of gambling’, The American Journal of Sociology, 57(3), pp. 215-21.

Boyd, W.H., 1976. ‘Excitement: The gamblers drug’, in W.R. Eadington (ed.) Gambling and Society: Interdisciplinary

Studies on the Subject of Gambling. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

Brandewie, E., 1967. ‘Lucky: Additional reflections on a native card game in New Guinea’, Oceania, 38, pp. 44-50.

Brenner, R. and Brenner, G.A., 1990. Gambling and Speculation: A Theory, a History, and a Future of Some Human Decisions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Brunk, G.G., 1981. ‘A test of the Friedman-Savage gambling model’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 96(2), pp. 341-48.

Burton, M.L. and White, D.R., 1987. ‘Cross-cultural surveys today’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 16, pp. 143-60.

Busche, K. and Hall, C.D., 1988. ‘An exception to the risk preference anomaly’, Journal of Business, 61(3), pp. 337-46.

Chick, G., 1984. ‘The cross-cultural study of games’, Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 12, pp. 307-37.

Chick, G., 1997. ‘Cultural complexity: The concept and its measurement’, Cross-Cultural Research, 31(4), pp. 275-307.

Chick, G., 1998. ‘Games in culture revisited: A replication and extension of Roberts, Arth, and Bush (1959)’, Cross-Cultural Research, 32(2), pp. 185-206.

Codere, H., 1950. Fighting with Property: A Study of Kwakiutl Potlatching and Warfare 1792-1930, J.J. Augustin Publisher, New York.

Cooper, J.M., 1941. Temporal Sequence and the Marginal Cultures, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC.

Cooper, J.M., 1949. ‘Games and Gambling’, in J.H. Steward (ed.) Handbook of South American Indians. Smithsonian Insitution, Washington, DC, 503-24.

Culin, S., 1894. ‘Mancala, the National Game of Africa’, Annual Report of the U.S. National Museum, pp. 597-606.

Culin, S., 1899. ‘Hawaiian games’, American Anthropologist, 1(2), pp. 201-47.

Culin, S., 1907. Games of the North American Indians (1975 reprint), Dover, New York.

de Borhegyi, S.F., 1980. The Pre-Columbian Ballgames: A Pan-Mesoamerican Tradition, Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee.

DeBoer, W.R., 2001. ‘Of dice and women: Gambling and exchange in native North America’, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 8(3), pp. 215-68.

Douglas, M., 1970. ‘Introduction: Thirty years after “Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic”’, in M. Douglas (ed.) Witchcraft: Confessions and Accusations. Tavistock, London.

Downes, D.M., Davies, B.P., David, M.E. and Stone, P., 1976. Gambling, Work and Leisure: A Study Across Three Areas, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Driberg, J.H., 1927. ‘The game of Choro or Pereauni’, Man, 27, pp. 168-72.

Eaglesmith, J.C., 1976. ‘The native American ball games’, in M. Hart (ed.) Sport in the Sociocultural Process. Wm. C. Brown Co. Publishers, Dubuque, Iowa.

Edwards, W., 1954. ‘The theory of decision making’, Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), pp. 380-417.

Elias, N. and Dunning, E., 1970. ‘The quest for excitement in unexciting societies’, in G. Lüschen (ed.) The Cross-Cultural Analysis of Sport and Games. Stipes, Champaign, Ill.

Ember, C.R. and Ember, M., 1998. ‘Cross-cultural research’, in H.R. Bernard (ed.) Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology. AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Ember, C.R. and Ember, M., 2001. Cross-Cultural Research Methods, AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Erasmus, C.J., 1950. ‘Patolli, pachisi, and the limitation of possibilities’, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 6, pp. 369-87.

Forrest, D., Simmons, R. and Chesters, N., 2002. ‘Buying a dream: Alternative models of demand for lotto’, Economic Inquiry, 40(3), pp. 485-96.

France, C.J., 1902. ‘The gambling impulse’, American Journal of Psychology, 13, pp. 364-407.